Scene: a London hospital bed occupied by Ronnie Scott, legendary club owner poleaxed by a rogue spinal disc. When a concerned visitor asks the cause of Scott’s problem. Scott replies through gritted teeth: “bending over backwards to please Stan Getz”.

Nobody would have called Stan Getz an easy-going guy (on learning that Getz had undergone heart surgery, fellow saxophonist and former colleague Zoot Sims asked “did they put one in?”). Although constantly plagued by demons, Getz played the tenor saxophone like an angel. His unstoppable torrent of ideas wrapped in sumptuous sound led John Coltrane’s to comment “let’s face it, we’d all play like Stan Getz, if we could”.

A professional musician from age 16, Getz began as a devoted disciple of Lester Young, maestro of laid-back jazz. Eventually, by the time he became star soloist with Woody Herman’s celebrated Four Brother’s band in the late 1940s, he’d reworked and polished the Prez’s influences into a unique approach, understated yet emotional, relaxed yet swinging. Instantly identifiable, Getz became the moody pin-up boy of the cool movement.

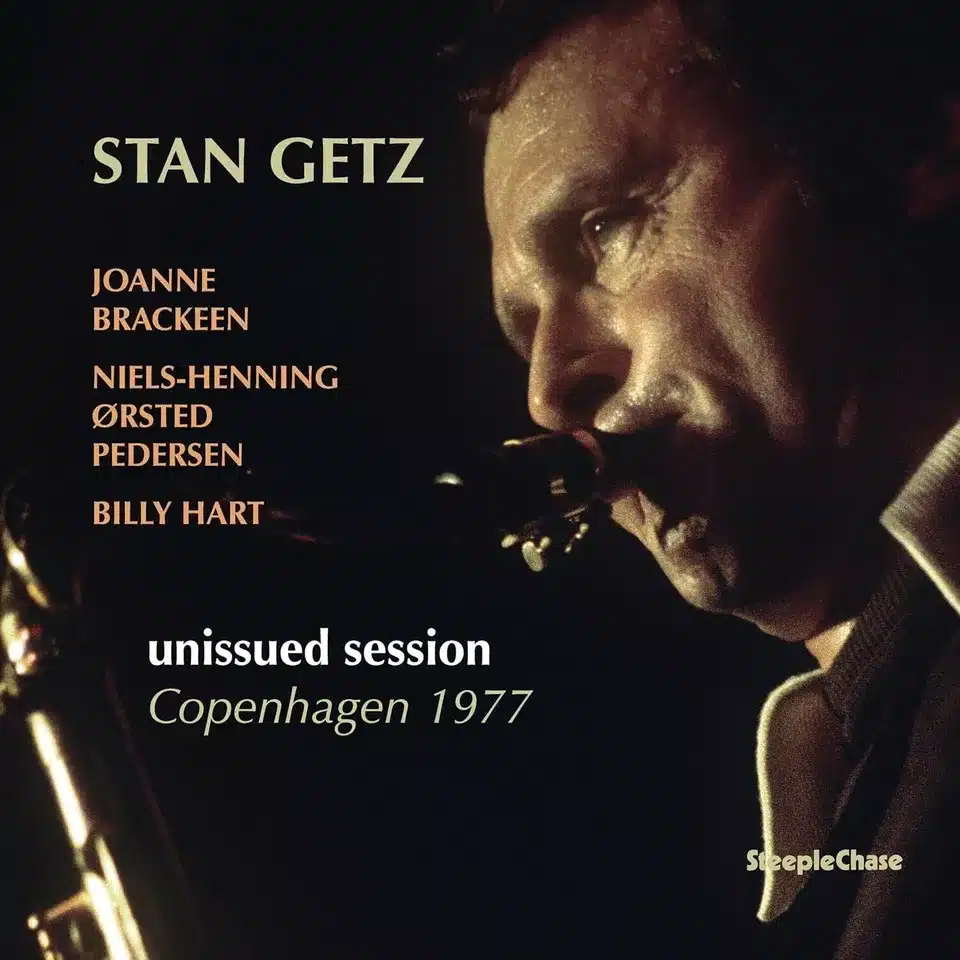

Over the decades, the iciness slowly thawed and his exquisite tone matured like fine Armagnac, gaining richness and complexity. On this album, taped in Copenhagen in January 1977, in the days leading up to the saxophonist’s 50th birthay on 2 February, yet inexplicably destined to languish in some cobwebby cupboard until 2024, we find Getz in thrilling form, clearly relishing the megawatt company of pianist Joanne Brackeen, drummer Billy Hart and virtuoso Danish bassist, Niels-Henning Ørsted Pedersen. Although this was the first time they ever worked together as a unit and most of their material was unfamiliar, the level of responsive interaction among the four musicians could persuade sceptics to believe in supernatural forces. The band opened at Copenhagen’s renowned Jazzhus Montmartre on 29 January and the tape of their first night, issued as ‘Live at Montmartre Volumes 1 & 2’ is a personal favourite in the collection of Seb, our esteemed editor. Some of the performances that weren’t included on that album are picked up here, as well as the complete studio session recorded on 30 January.

After touring South America during the early sixties, Getz helped establish Bossa Nova as a global fad and, to remind us of his key rôle, the album opens with Milton Nascimento’s Cancāo Do Sal, a politicised musical tribute to the salt workers in Brazil. On this album, we’re provided the opportunity to hear how the nascent quartet gets to grips with the piece because track one, a studio recording, happens to be the first-ever take. Takes 2 and 3, both live, are also included on the album demonstrating how this combination of brilliant professionals tackles the composition’s shifting shape and tricky changes. On all three versions Brackeen plays electric piano with ravishing solos on Takes 1 & 2 (no keyboard solo on Take 3). We hear Billy Hart digging deeper and deeper into the song as he absorbs and digests the sinuous and eccentric rhythms. And, as ordinary mortals, we can only marvel at the miraculous precision of Ørsted Pedersen’s uncanny intonation on every take and every track. Needless to say, throughout the album, Getz is incapable of playing an inelegant phrase (on the other hand, did he ever?).

Among the riches on offer, we’re treated to two takes of Blue Serge, a fine piece ostensibly written by Duke’s son, Mercer Ellington, during the 1940’s ASCAP strike which temporally prevented his dad from recording any compositions under his own name (interestingly, when the dust settled after the strike, Mercer never seemed to write anything as classy again). Whatever, Getz begins the song with an unaccompanied heart-rending cry, intensifying its minor key sadness. Brackeen, now on acoustic piano, extends the melancholic bluesy mood, yet manages to add elegant keyboard flourishes with unerring support from Ørsted Pedersen. Both takes are worth the money.

The album contains a brace of tributes to two jazz immortals: Billie Holiday and Clifford Brown. The first is Lady Sings The Blues written by Holiday together with pianist Herbie Nicholls’ (although it’s correctly attributed in Neil Tesser’s informative sleeve notes, it’s not Alec Wilder’s tune as erroneously claimed on the back of the album). Getz treats the moving theme with obvious passion while Ørsted Pedersen’s stealthy bass places absolutely the right note in the right place at the right time, every time. Brackeen contributes a sensitive and apposite commentary until she’s free to express fervent admiration in a stunning solo.

The second tribute is Getz’s initial recording of I Remember Clifford, Benny Golson’s poignant dedication to the late Clifford Brown, the stellar young trumpeter whose career was ended by a car crash. Brackeen pitches a brief intro into the fizzing atmos of Jazzhus Montmartre before Getz invests his reading of Golson’s melody with a weight of emotion rendering any further elaboration irrelevant. Getz was so deeply affected by I Remember Clifford that he retained it in his concert repertoire until his final appearances.

The pace lifts with Quiso, a lively piece by Canadian-born Kenny Wheeler, composer and trumpet player who long graced the UK jazzscape. Getz runs long post-bop phrases and hands the baton to Brackeen who maintains the mood before shifting into urgent flurries of notes before ushering Ørsted Pedersen’s masterly advanced course in the art of pizzicato. Then back to the ensemble and a brusque ending on a lone saxophone note.

On Chick Corea’s Litha, also recorded during live performance at Jazzhus Montmartre, Brackeen reverts to electric piano while Ørsted Pedersen and Billy Hart move lithely between the alternating rhythms and tempi with never a misstep. High points include Getz’s breathtaking virtuosity and Brackeen’s elegant keyboard inventions, all elevated to the highest level by Ørsted Pedersen’s pace-making bass.

We should all be grateful to Freddy Hansson and Hans Nielsen, the original recording engineers, for putting all this music on tape. And we should be even more grateful to producer Nils Winther for taking these old tapes from their forgotten corner, dusting them off and reviving them so expertly that we could eavesdrop on giants at play.