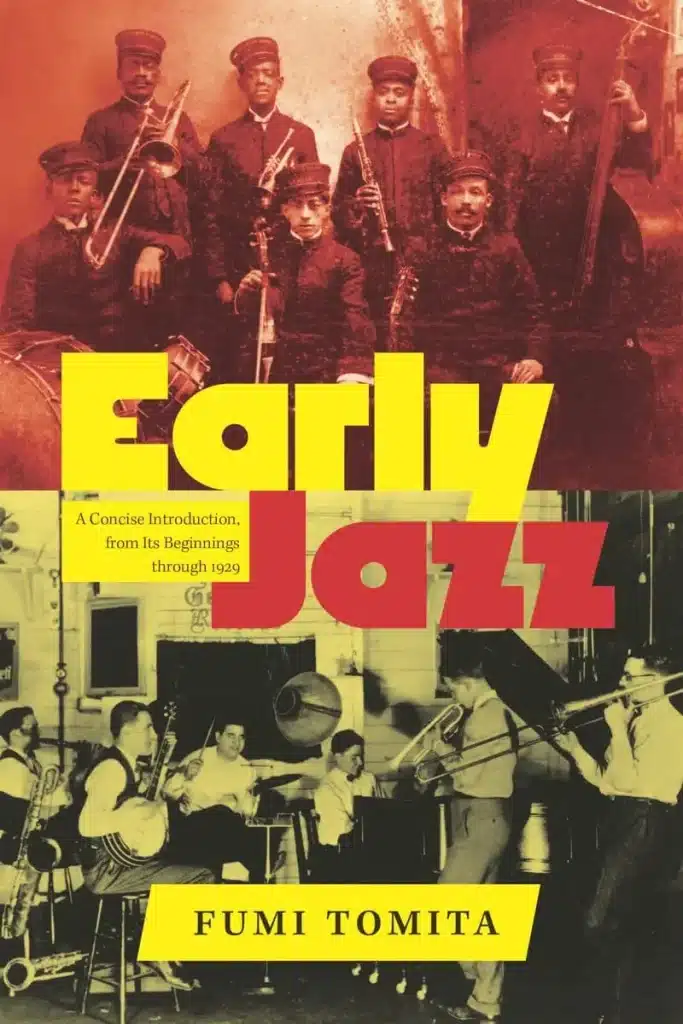

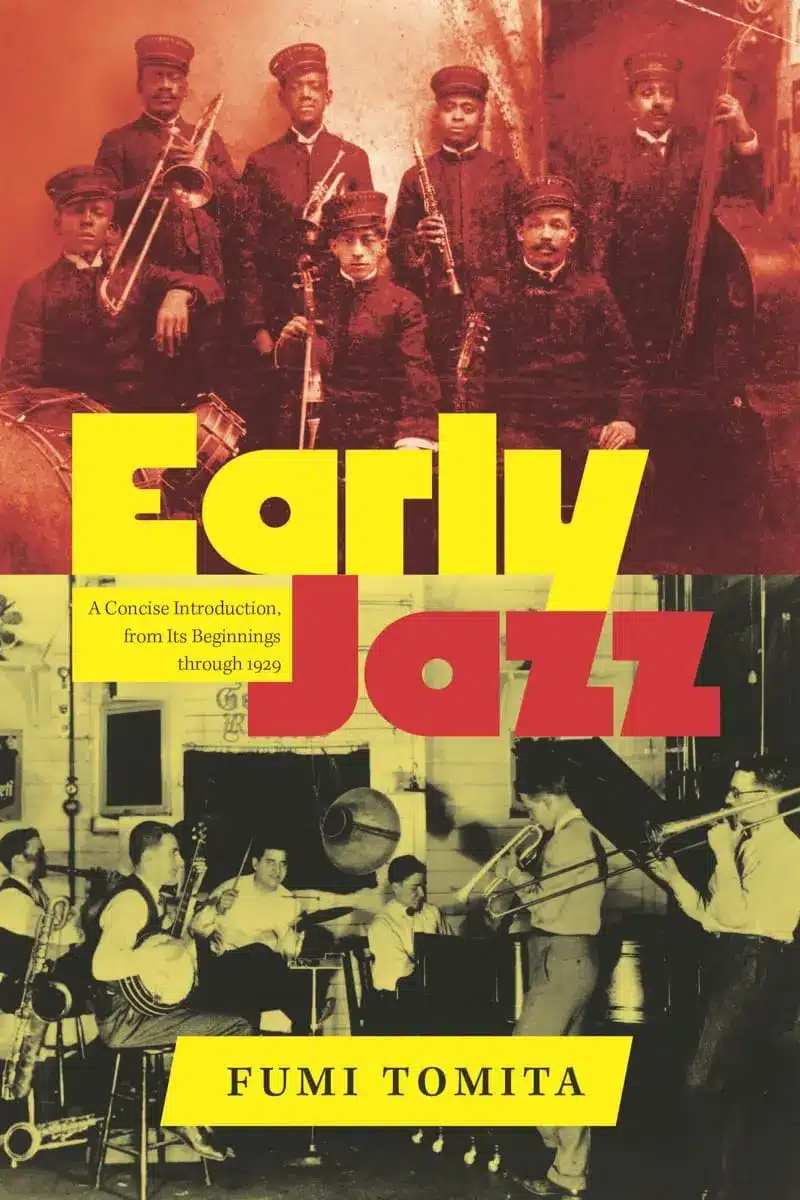

Early Jazz: A Concise Introduction, from Its Beginnings through 1929, by Fumi Tomita.

(SUNY Press, 232pp. Book review by Andy Hamilton)

Fumi Tomita teaches jazz at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst, and was active as a bass player in the New York jazz scene for over fifteen years. His Early Jazz is a history of jazz from its nineteenth-century roots through to 1929, when the Swing Era began to emerge. It’s the first comprehensive history of early jazz since Gunther Schuller’s classic title from the 60s, and Tomita sees his book as in some ways an update of it. Unlike Schuller, Tomita fully embraces entertainment as well as art. Musicians covered include pioneering African American and white musicians but also entertainers or novelty performers, and American jazz musicians who introduced jazz on their travels round the world. Twenty songs are analyzed in depth, but – unlike with Schuller – no musical knowledge is required. The non-technical Listening Guide analysis includes such tracks as King Oliver’s Snake Rag, Frank Trumbauer’s Singin’ The Blues, and Lovie Austen’s Traveling Blues.

The book is an update of Schuller, the author says in an online interview, “in the sense that…the non-specialist could more easily digest the material.” Schuller’s book helped establish jazz as music worth studying, but Tomita wanted to draw on current research, such as Brian Harker’s work on Armstrong and his Hot Fives and Sevens. He avoids Schuller’s approach of using transcription, and presents early jazz as a combination of art and entertainment music: “that’s what jazz really is—sometimes it’s more art and other times it’s more entertainment and the jazz musician is capable of playing both.” He wanted to offer a corrective to jazz history in its traditional sense: “jazz history is not only male heavy, but also trumpet-saxophone-piano heavy!”

By email, Tomita explains that “Schuller was part of a group of writers who eventually succeeded in gaining respect for jazz – it’s now taught at colleges and universities and is represented in Washington, etc. Anything commercial might have threatened that agenda. Jazz was considered ‘low’ entertainment, so the thinking was to let the world know about the artistry of jazz improvisation (and composition). I think it is safe to talk about those things that were previously discarded.” He adds that, “I think those novelty sounds stayed in the music, as the idea of sounding like an individual player resonated very strongly from the bebop era – though musicians were now playing the instrument ‘properly’, no gaspipe clarinet or kazoo.”

Jazz developed out of the entertainment world of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, Tomita argues – minstrelsy, circuses, carnivals and vaudeville: “There were no jazz clubs, it was just dance halls and you played for dancers…Relying on recordings only presents a skewed picture of the music.” He discusses the complex racial situation in New Orleans, arguing that white and black players learned from each other. “The most prominent white ethnic group in early jazz were Italians”, he explains. He describes the significant subgroup of Arbëreshë, descendants of Albanian refugees who came to Italy in the 15th century and who retained their language and religion, and also Afro-Italians.

The familiar names are discussed – Scott Joplin, Bessie Smith, Buddy Bolden, the ODJB, King Oliver, Jelly Roll Morton, James P Johnson, Armstrong, Ellington and others – but also many lesser known ones. For instance, Adrian Rollini is properly acknowledged as an unsung hero of early jazz. He used a baritone mouthpiece to improve the playability of his unwieldy bass saxophone, though he gradually discarded this instrument in favour of the vibraphone. The full range of Fats Waller’s achievement – including on his favourite instrument, the pipe organ – is explained. The Chicagoans are well-discussed. Frankie Trumbauer was one of the earliest saxophonists to dispense with the slap-tongue technique in favour of a legato one, Tomita explains.

I learned a lot from this book, which is succinct and well-written. For instance, Tomita convincingly compares Alberta Hunter and Bessie Smith, the latter having a “strongly African American character…from the church and blues…untouched by any white influence (p. 28). Buddy Bolden “was primarily an ear player, an approach that nurtured an interpretive manner of playing or reading music that spells improvisation” (p. 36). I didn’t realise that Ellington’s “Creole Love Call” is in fact King Oliver’s “Camp Meeting Blues” from 1923. And I had no idea that Paul Whiteman had nineteen orchestras working out of his office, that extended internationally with tours of Europe in 1923 and 1926. Tomita well describes Whiteman’s brand as “polite jazz” that had evolved from “crude” beginnings to become a “respectable” artform.

Tomita debunks the traditional history of scat – it had been practised by comedians for at least a decade before Armstrong dropped his sheet-music on “Heebie Jeebies”. Tomita stresses that Armstrong was an entertainer at heart, and never understood the acclaim given his Hot Five and Hot Seven recordings. The book is overall a very enjoyable read, and I hope that Tomita continues his Schuller-like progress – and indeed that, unlike his mentor, he eventually completes his history of jazz.

Publication date 2 August 2024

Buy / Pre-Order Early Jazz from Presto Music

One Response

” also many lesser known ones. ” ….. but no mention of Jabbo Smith?

“Jabbo Smith had a short but important recording career in the late 1920s when he became the first trumpeter to seriously challenge Louis Armstrong with a virtuosity years ahead of its time.”

https://riverwalkjazz.stanford.edu/program/ace-rhythm-story-jabbo-smithtrumpeter-composer