Sometimes it feels like the history of jazz is propelled solely by innovators and entrepreneurs, a series of formidable iconoclasts who stand like beacons whilst lesser musicians, commonly known as “great players”, emulate and accumulate. Historians often favour that kind of synopsis, but I often find that the next generation, those that come after the revolutionary voices, often feel freer to blend in their own personal influences, giving rise to a more hybrid and nuanced sound.

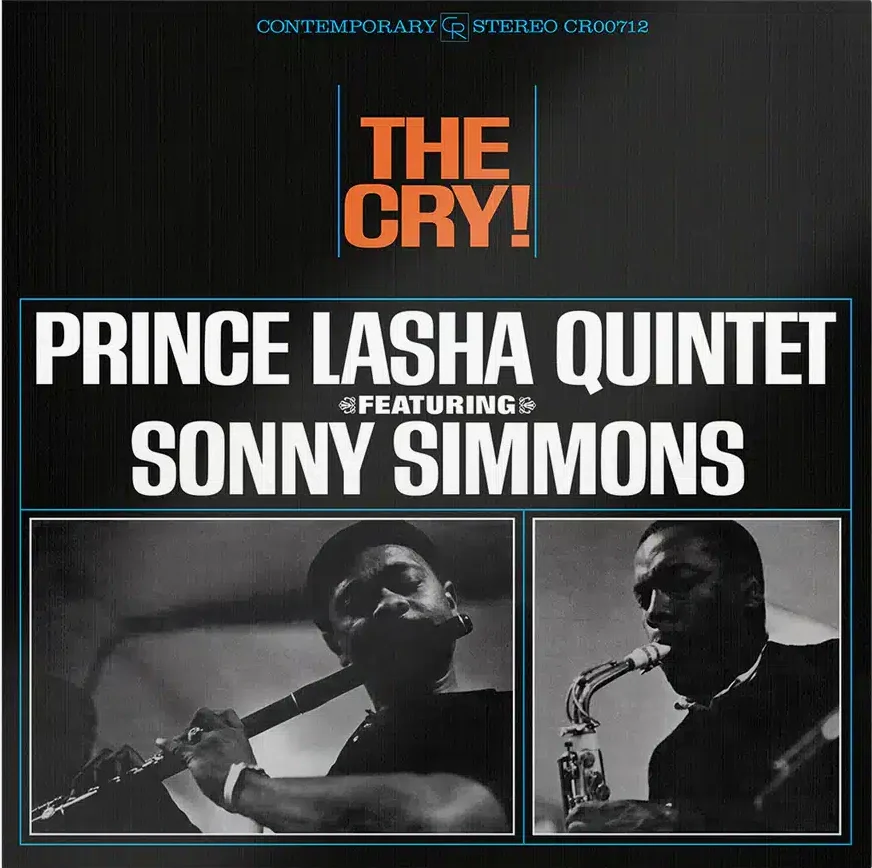

Lester Koening, in his learned notes (people don’t often mention “the stultifying effects of cadential formulas” these days) spends a long time talking about Ornette Coleman. It’s understandable: Coleman grew up in Fort Worth, Texas, and studied music alongside Prince Lasha, the flautist and composer who leads this session. Sonny Simmons, the Louisiana-born altoist featured here, has absorbed plenty of Ornette’s sound and approach, but was inspired first by Bird. Everything I have read about this recording talks first about Ornette’s approach, then ushers in Lasha’s music as if giving it permission to exist. I braced myself for some kind of pastiche.

The opening track, “Congo Call”, could not be further from what I expected: a one chord vamp, made extraordinary by two basses in octaves and the bracing combination of Lasha and Simmons. Its asymmetrical melody reflects Ornette’s rejection of standard forms, but the Gnawa-like throb of the bass and drums comes closer to Coleman’s cohort Don Cherry in its immersive approach. Prince Lasha’s lines have a gentle, blossoming lilt in contrast to the cut of Simmons’s alto, with “Bojangles” and “Lost Generation”, both trios with Simmons, bassist Gary Peacock and drummer Gene Stone, showing how he took Bird’s language and stirred a little Dolphy and Ornette into it. The end result is that he wears his influences on his sleeve but, in places like the lengthy solo introduction to “The Lost Generation”, he sounds like no one else.

Throughout, the compositions (attributed to both the leaders, but with no further details supplied) do indeed have one connection to Ornette, and its one that is often overlooked: the catchiness of the themes. Some, like “Ghost Of The Past” have a Joe Harriot-like simplicity that is almost laugh-out-loud funny (as well as what sounds to me like an uncredited bass clarinet in the head arrangement), and “Green And Gold” has a charming lope that is offset by the presence of two basses, giving it the sense of textured counterpoint found in so much African music. “Juanita” has a similar charm in its simplicity and features a theme that seems to gradually chip away at itself until it finds its final note.

It’s a strange record historically: Lasha gets top billing, but its Simmons who gets most of the solo space, including those two trio tracks to himself. Bassist Mark Proctor and drummer Gene Stone didn’t quite go on to make the mark that Gary Peacock did (and you can hear Peacock bursting out of the texture throughout this album). But the rhythm section is incredibly effective throughout, the slight chugginess of Stone’s drumming and the solidity of Proctor’s basslines enabling the others to duck and dive without the wheels coming off.

Perhaps that’s the main connection with Ornette: the idea that music doesn’t come from virtuosity but relationships, from specific combinations of people. If you get that right, the ideas will come. And this record is full of them.

One Response

https://jazzflits.nl/jazzflits18.15.pdf

dear jazzfriends,

can you give this to Liam Noble ?

I wrote a study about Prince Lasha –

from Belgium,

Erik Carrette