South Africa has become a reliable source of emergent jazz talent in the last few years. Blue Note records’ fabled roster now includes artists such as saxophonist Linda Sikhakhane and pianist Nduduzo Makhathini. UK-based players like Shabaka Hutchings have sought out young South African collaborators. And the work of South Africans who endured exile during the horrors of apartheid, like Abdullah Ibrahim, Hugh Masekela or Chris McGregor, continues to inspire.

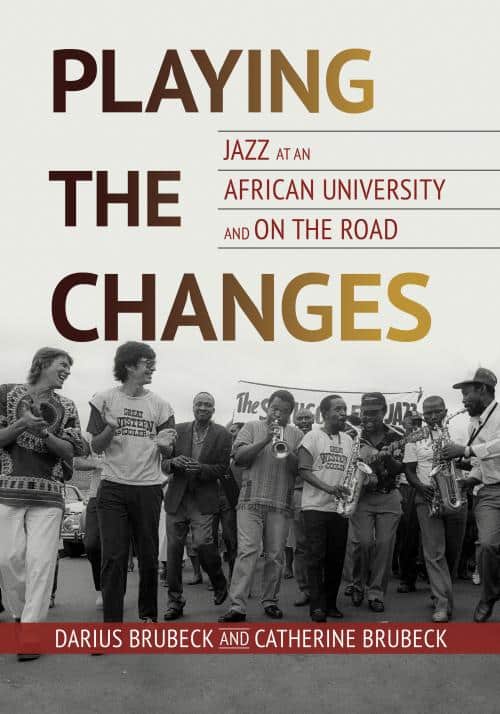

Yet the decades spanned by these old and new names also saw many players who kept jazz alive inside the country, but whose stories were never visible to the wider world. Darius and Catherine Brubeck’s book recovers that history in rich detail.

They are uniquely placed to write it because Darius took up an appointment at the University of of KwaZulu-Natal in Durban 40 years ago. By the time he left, two decades later, he and Catherine – who worked mostly unpaid – had launched the first jazz studies course in the country and nurtured its growth into an established university centre that was ripe for handing over to South African teachers in the by now fully-enfranchised republic.

Their dual narrative is carefully put together from their own recollections, archive materials, and interviews with surviving students, colleagues, friends and fellow activists. Together they underline what a remarkable project they carried off.

Catherine was clearly crucial to the whole enterprise of establishing a jazz education centre in a milieux where the boundaries between jazz as creative art and as agitation were largely dissolved. But the public presence of the university’s effort relied heavily on her partner’s commitment to the university as the star recruited from the USA, and his willingness to take advantage of his world famous name.

Darius, the eldest child of Dave and Iola Brubeck, may be the best adjusted son of a legend you will ever come across. A musician first and foremost, he is almost relentlessly modest: “I never saw myself as an outstanding pianist. I know how to work with what I’ve got.” Lately, as UK audiences know, Darius in performance delivers classic tunes by his father, as well as his own compositions and pieces from South Africa. But musical prowess aside, he brought other outstanding qualities that served the political and cultural project of South African jazz. He and Cathy together evidently deployed a rare mix of diplomatic, administrative, organisational and entrepreneurial skills, along with a prodigious capacity for work, in service of a commitment to activism that was in line with Brubeck family values.

Different readers will take different things from this book. Your reviewer, as it happens, has launched new university courses in subjects new to institutions – possibly the only thing Darius Brubeck and I have in common – so I found it intriguing how much of the formal business, and the informal invention of ways of getting things done in a university in a colonised country, was familiar. But the context, of course, was radically different. This was a university in a period of political ferment, recruiting jazz students with few or no formal qualifications and usually no money, in a country where a campus concert or a night at a mixed race jazz club might proceed untroubled, but was equally likely to be broken up by police wielding whips, or worse. The round of politicking, committee work, fund-raising, finding places for students to live and getting them to abide by university routines, actual teaching, not to mention a continual pursuit of gigs as a showcase for the university and the course, never seemed to let up. Add overseas visits and eventually international tours for ensembles rooted in the university, and the workload must have been relentless.

All this in a place and time when a band booked for a gig could find it was suddenly down one player because a (white) musician had skipped the country to avoid service in South Africa’s National Defence force, or an application for a part-time teaching position might go:

Current or past employer: African National Congress

Type of Organisation: Liberation Movement

Position Held: Guerilla

But they held it all together against the odds, and many students, teachers, and students who became teachers, went on to flourishing careers in music and music education. All of them are remembered here, and much of the detail of gigs, venues, institutions, and personnel will mainly be of interest to readers in South Africa looking for a first-hand first draft of this history (the book was originally published in South Africa last year). There are also insights into players who gained fame internationally, like the rarely gifted Zim Ngqawana. His time as a student led to a deep and long-lasting friendship, albeit with reservations about his aspiration to become the guru of “Zimology”. Among his other attributes, Darius is a keen reader of character and, once read, his description of Zim in the 1990s learning to “turn on an air of aggrieved superiority just like Abdullah” (Ibrahim), whose band he had then joined, is unlikely to be forgotten.

Ibrahim is still with us, but Zim, like many of the others portrayed here, died prematurely. The book is a fitting memorial to all those the authors worked and lived with, and leaves one eager to hear the music that comes from this musically fascinating country in future.